Note to Readers: This article first appeared in the “Voices” section of National Mortgage News

They say on Wall Street that bull markets do not die of old age. The same might be said of the commercial real estate market (CRE), which has experienced its own decade-long bull run and, according to industry pundits, shows few signs of running out of steam. Or has it? As we look at the overall CRE market with rose-colored glasses, we might overlook current stresses that are wearing down the foundations of the cyclical expansion in the massive, small-cap CRE market.

Small-cap CRE accommodates 30 million U.S. small businesses with modest-sized owner-occupied and leased facilities and consists primarily of small office, industrial and retail buildings typically sized under 50,000 square feet and below $5 million in value. However, this market currently faces two distinct challenges in space and labor scarcity, which have alarmingly intertwined to hamstring facility expansion needs increasingly over the past two years. These obstacles, in turn, pose the potential for significant ramifications in the high-octane, small-balance commercial loan market that—according to Boxwood Means’ research—generated $200 billion of originations during 2019.

Extremely low vacancy rates present the first challenge for small businesses. Granted, as a real estate cycle matures, space scarcity is not an uncommon occurrence when continuous high levels of demand meet sluggish new supply. However, this time around, the magnitude of the shortage certainly is unusual. The aggregate U.S. small-cap vacancy rate was just 4.3 percent on average across the three property types last year and a record 200 basis points below its nadir before the Great Recession, according to Boxwood’s analysis of CoStar data. Expect very little wiggle room in the space market when national vacancy rates for small-cap warehouse and flex building vacancies plummet to roughly 3 percent, neighborhood/strip centers and general retail slim down to 4 percent and office vacancies to 6 percent while, significant deliveries of newly constructed buildings for lease fail to kick in. That is precisely the conundrum in the small-cap market today. Small office and industrial businesses and tenants, especially near the urban core, are largely cut off from viable expansion or new leasing opportunities.

But arrested expansion opportunities caused by historically low vacancy rates is only one half of the scarcity equation. The shrinking labor market is the other major limiting factor.

It's well-known that the national unemployment rate is at a historic low point. What is less well-known, however, is that small businesses tend to suffer the consequences of labor shortages earlier and perhaps more keenly than bigger firms. For example, for much of 2019, the National Federation of Independent Business’s (NFIB's) monthly economic surveys consistently reported that many small business owners were unable to find qualified workers to fill open positions —in fact, they named this condition their top concern. Furthermore, using ADP payroll data, Moody’s Analytics found that employment levels at firms with less than 20 workers were largely unchanged last year – the first time these annual payrolls were flat since 2010. By contrast, companies with 500 or more employees grew headcount last year by 2.3 percent.

×

![]()

The combined impact of labor and space scarcity has taken a sizable toll on small-cap CRE operating fundamentals and, specifically, on space-demand trends. This 'double whammy' effect has precipitated a 70 percent year-over-year plunge in net absorption across the three property types, and the roughly 40 million square feet of aggregate small-cap demand last year was the lowest amount since the end of the Great Recession in 2009. Even the much-hyped industrial market, where space market fundamentals significantly outperformed office and retail sectors for several years running, recorded a massive 95 percent pullback year-over-year in positive net absorption—punctuated by rare net negative absorption in three of the four quarters (the Q4 negative absorption total is preliminary).

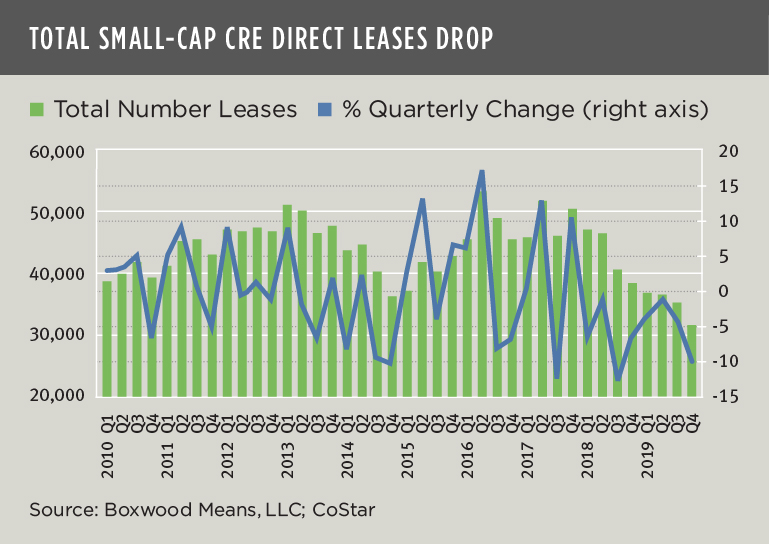

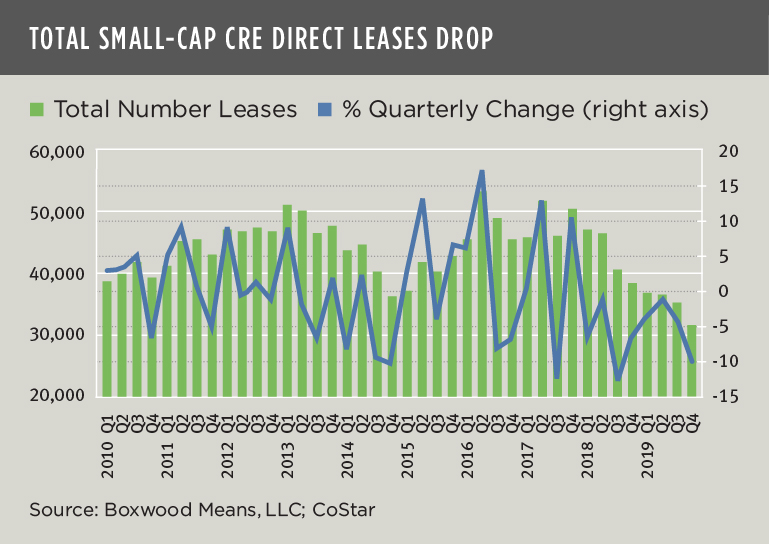

Adding to this notable retreat is the most telling demand-related trend of all—the precipitous decline in small direct leases signed. As the nearby graph shows, the number of small-cap office, industrial and retail leases fell for eight consecutive quarters to 140,000 lease deals during 2019; in other words, the lowest total since the first quarter of 2009! Not surprisingly, rent growth is slowing.

Real estate analysts know that positive net absorption is not only the key driver to the stability and continued growth of the space market, but also a principal factor in the market for income-producing real estate. And while the low interest rate regime has played a major role in higher asset valuations, it is space market fundamentals that support rent and net operating income (NOI) growth that ultimately will sustain CRE asset prices going forward.

Boxwood’s research further indicates that small-cap CRE asset values rose 5 percent nationally last year, topping the pre-recession peak by nearly 10 percent. At these heights, small-balance lenders and investors need to be mindful this year of the potentially volatile and risky mix of lofty property prices and declining operating fundamentals that has emerged.

Unless market participants further elevate their due diligence and underwriting of property valuations, it is a sure bet that many late-cycle small-balance loan originations will leave borrowers with excessive debt relative to cashflow if space market fundamentals continue to contract.

Perhaps on Wall Street and Main Street, bull markets do not die of old age. But as Winston Churchill once said, “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”